Recognition of Procrastination as a Trauma Response: How to interrupt it.

Discover the recognition of procrastination as a trauma response, its psychological roots, real-world signs, and evidence-based healing strategies for long-term recovery.

Recognition of Procrastination as a Trauma Response

The recognition of procrastination as a trauma response marks a critical shift in how mental health professionals, educators, and individuals understand avoidance behaviors. For decades, procrastination has been framed as laziness, poor time management, or lack of discipline. However, modern psychology increasingly acknowledges that procrastination can be a protective survival response rooted in unresolved trauma.

When the nervous system perceives a task as unsafe—emotionally, psychologically, or socially—it may activate a freeze response. This causes shutdown, avoidance, or paralysis. From the outside, this looks like procrastination. From the inside, it feels like fear, overwhelm, or numbness.

Understanding this distinction is not about excusing behavior; it’s about healing the root cause rather than punishing the symptom.

Types of Trauma Linked to Chronic Procrastination

Childhood Trauma

Experiences such as emotional neglect, harsh criticism, or unpredictable caregivers teach the brain that mistakes are dangerous. Tasks associated with evaluation can later trigger freeze responses.

Workplace and Academic Trauma

Burnout, public shaming, unrealistic expectations, or repeated failure can condition the nervous system to associate work with threat.

Medical and Relational Trauma

Chronic illness, abusive relationships, or sudden losses can erode a sense of control, making future planning feel unsafe.

The Psychology Behind Trauma Responses

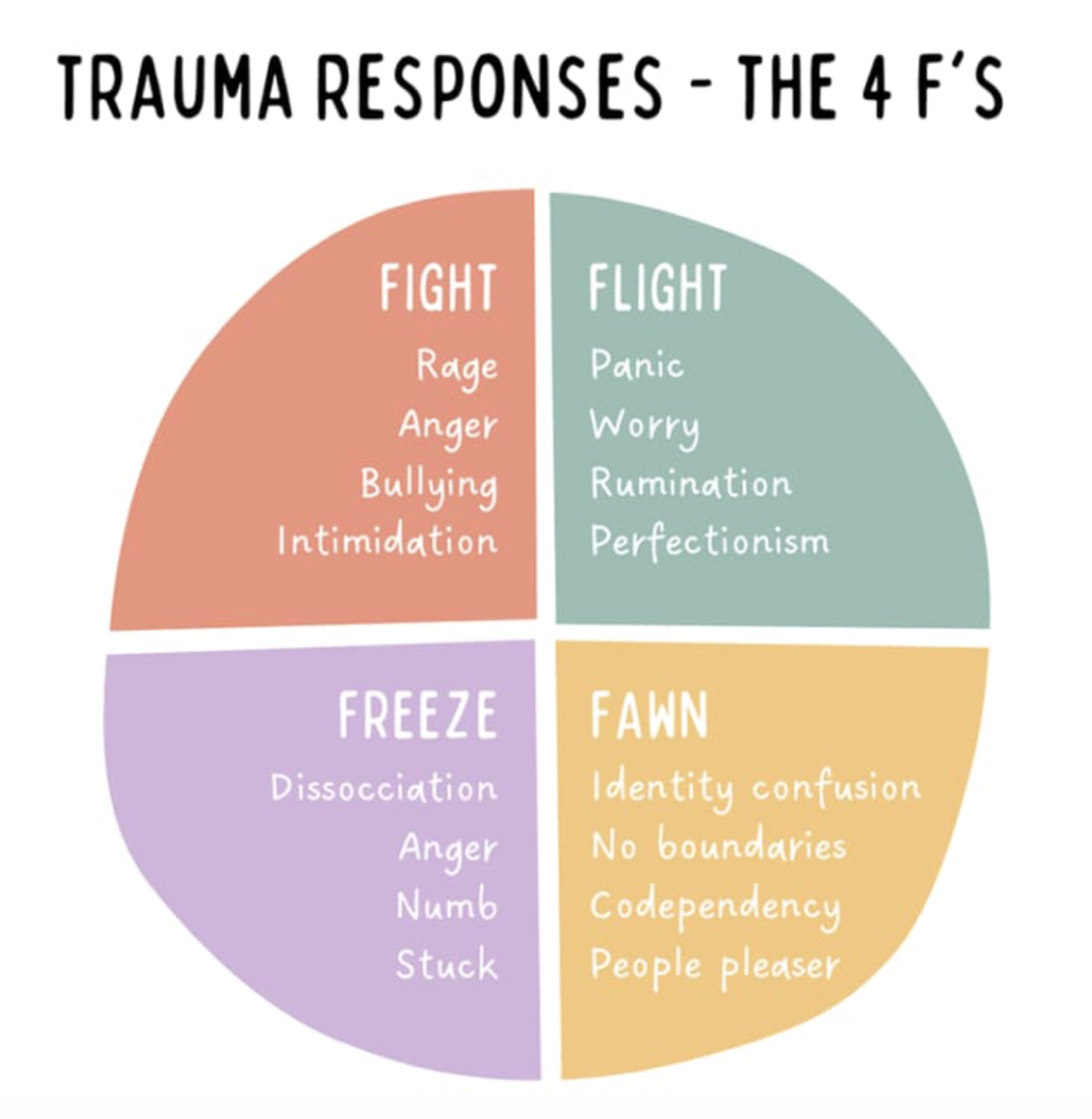

Fight, Flight, Freeze, and Fawn Explained

The human stress response includes four primary survival modes:

Fight: Confronting perceived danger

Flight: Escaping or avoiding

Freeze: Shutting down or becoming immobilized

Fawn: People-pleasing to maintain safety

Procrastination is most commonly linked to freeze and flight responses.

Why Freeze Often Looks Like Procrastination

Freeze occurs when escape feels impossible and confrontation feels dangerous. The body conserves energy by shutting down. Cognitively, this results in:

Brain fog

Difficulty initiating tasks

Dissociation or numbness

This is why people often want to act but feel physically unable to start.

How Trauma Rewires the Brain

The Role of the Nervous System

Trauma sensitizes the amygdala (threat detector) and weakens the prefrontal cortex (planning and decision-making). When a task resembles past danger—such as evaluation, deadlines, or authority—the brain reacts as if survival is at stake.

Survival Mode vs Productivity Mode

Productivity requires safety. Trauma places the body in survival mode, where long-term goals are deprioritized. No planner or to-do list can override a nervous system that believes it is under threat.

Common Signs of Procrastination as a Trauma Response

Emotional Indicators

Intense anxiety before simple tasks

Shame disproportionate to the task

Fear of being seen or judged

Emotional numbness or shutdown

Behavioral Patterns

Avoiding emails, paperwork, or decision-making

Waiting until the last possible moment

Starting but never finishing tasks

Overpreparing to avoid failure

These patterns persist even when motivation is high.

Misdiagnosis: When Procrastination Is Mistaken for Laziness

Shame, Guilt, and Self-Blame Cycles

When trauma-based procrastination is mislabeled as laziness, individuals internalize shame. Shame increases stress, which reinforces freeze responses—creating a self-perpetuating loop.

This is why harsh self-discipline often worsens procrastination instead of fixing it.

Healing Through Recognition and Self-Compassion

Nervous System Regulation Strategies

Effective healing begins with safety. Evidence-based tools include:

Deep, slow breathing

Grounding exercises

Gentle movement

Predictable routines

These signal to the body that the present moment is safe.

Trauma-Informed Productivity Tools

Instead of rigid schedules, trauma-informed approaches emphasize:

Flexible deadlines

Choice and autonomy

Low-pressure task initiation

Rest as a non-negotiable need

Productivity becomes a byproduct of regulation, not force.

Practical Daily Strategies to Overcome Trauma-Based Procrastination

Micro-Tasks and Safety Cues

Breaking tasks into extremely small steps reduces threat perception. For example:

Open the document

Read one sentence

Write one word

Pair tasks with safety cues like calming music or familiar environments.

Boundaries and Rest

Overworking reinforces trauma patterns. True recovery requires respecting limits and recognizing that rest is a biological necessity, not a reward.

Body Doubling (must-have)

Working in the presence of another person—physically or virtually—can significantly reduce nervous system shutdown.

This works because the brain registers social safety, not accountability pressure.

Examples:

Studying quietly with a friend

Zooming with someone while both of you work silently

Sitting in a library or café instead of working alone

Time Containment (a.k.a. “Safe Time Boxes”)

Instead of open-ended work sessions, use clearly bounded time limits.

Trauma brains often freeze when tasks feel endless.

Examples:

“I’ll work for 10 minutes, then stop—no matter what.”

Use a timer and visibly end when it goes off

Short bursts are neurologically safer than marathon sessions

State-Before-Task Regulation

Before starting the task, regulate the body first, not after.

Trauma-based procrastination often isn’t about motivation—it’s about nervous system readiness.

Examples:

3 slow exhales before opening the laptop

Standing up and shaking out arms

Grounding feet on the floor before starting

Externalizing the Plan

Keeping the plan in your head increases cognitive load and threat.

Write or visually map everything outside your brain.

Examples:

Whiteboards

Sticky notes

Visible task lists with crossed-off micro-steps

Seeing progress externally reassures the nervous system that movement is happening.

Permission-Based Starts

Give explicit permission to start badly, imperfectly, or incompletely.

Perfectionism is often a trauma-based protective response.

Examples:

“This can be messy.”

“This is just a draft.”

“I’m allowed to stop halfway.”

When to Seek Professional Help

If procrastination severely impacts daily functioning, working with a trauma-informed therapist can help process underlying experiences and retrain the nervous system. Modalities such as somatic therapy and EMDR are commonly used.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychological Association. (2023). Procrastination: Why you do it, what to do about it. https://www.apa.org

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Gotham Books.

Coan, J. A., Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Lending a hand: Social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science, 17(12), 1032–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01832.x

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Martell, C. R., Dimidjian, S., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2010). Behavioral activation for depression: A clinician’s guide. Guilford Press.

McEwen, B. S., & Morrison, J. H. (2013). The brain on stress: Vulnerability and plasticity of the prefrontal cortex over the life course. Neuron, 79(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.028

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). https://www.nimh.nih.gov

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2010). Dissociation following traumatic stress. Journal of Psychology, 218(2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409/a000018

Sirois, F. M. (2014). Procrastination and stress: Exploring the role of self-compassion. Self and Identity, 13(2), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2013.763404

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Walker, M. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

World Health Organization. (2022). Burn-out an occupational phenomenon. https://www.who.int

Clinically Reviewed By: